The Cyclical Narrative

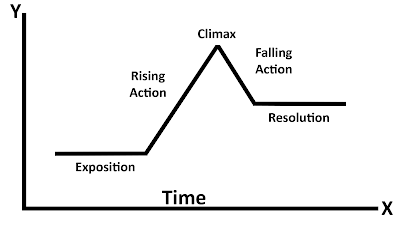

For most people the standard narrative arc will be quite familiar. In graph form it is akin to a parabolic curve with rising action, some climax moment, and falling action. While there may be differences in form from one story to another, there is one thing that remains constant throughout every novel, movie, play, or schoolyard story: the X-axis. Narrative time remains constant as one events leads to another in a strict, predictable, and sequential order. In the world of gaming, the linear narrative arc is no longer the only means of storytelling. Gaming is capable of expressing story through a cyclical story arc. In this form of story arc a portion of the narrative is allowed to loop, potentially into infinitum, with the events within the loop having narrative significance. In this essay we will examine the aspects, necessities, and significance of a cyclical story arc.

Figure 1: Linear story arc with axis.

There are three things that any narrative requires in order to present itself as a cyclical narrative. The first is that the narrative must form a continual cycle where it begins at one point, and ends at the same point. The second is that there must be some memory of past iterations so as to indicate that the narrative is a cycle instead of just having the player replay the same linear narrative. Finally, there must be at least two endings to the game, one constituting the end of the cycle and another the end of the game. Each of these aspects will be examined in greater depth.

Continual Cycle

Without a cycle there would be no cyclical narrative arc. Thereby, the first and most important aspect of a cyclical narrative is that, at some point in the narrative, the narrative must end at the same place it began. In doing so, the visualization of the narrative arc can be transformed into two different forms. One is a linear arc that points back towards its beginning. There are some benefits to visualizing the narrative in this way. It retains the same meaningful X-axis (that being time) as the common linear narrative, thereby allowing more simple comparison between the two. In addition, branching narratives within the cycle are easier to visualize. However, the method I choose to express the cyclical narrative is a circle. This is simply a line where the two ends have been brought together, making the end and the beginning indistinguishable. We will return to these visualizations later in this discussion.

Figure 2: Cyclical narrative arc expressed as a line. Includes branching narratives.

Figure 3: Cyclical narrative are expressed as a circle. C-End is the cycle's end while T-End is the true end.

There is more to the cycle than simply having the beginning and the end meet. There must be significant narrative elements between the start and end. In other words, some portion of the story has to happen inside of the cycle. Consider one example of a cyclical narrative: Everyday the Same Dream. The cycle in question is when the player chooses either one of the five alternatives to labor (see A Marxist Reading of Everyday the Same Dream) or to sit at their desk. Within the cycle are all of the major narrative element from committing suicide to petting a cow. The player cannot experience the narrative without engaging with the cycle.

The final note on the continual cycle is that it must be continual. In other words, every cyclical narrative must present the player with a way to loop the cycle infinitely. The reason for this returns to the graphs. In order for the cyclical narrative to have significance, it must not be able to be place meaningfully on a standard Euclidean graph. If all of the events that can possibly occur within the cycle can be written, with confidence, on a graph as a line (no matter the length of said line) then it remains a linear narrative. By presenting a way to infinitely loop the cycle, no person can ever write out the narrative (with confidence) as a simple line because that line could potentially reach into infinity. And yet it would almost certainly not go into infinity as the player would break the cycle eventually, hence no one can write the line with confidence.

Memory of Past Iterations

A cyclical narrative must be in some way distinguishable from simply restarting a game. This is where the memory of the past runs comes into play. The player must, in every cyclical narrative, have some way of determining within the game that previous iterations have occurred. There are two ways that cyclical narrative have done this in the past.

Environmental Ghosts

The most common method of showing the player the cycle is to leave ghosts of prior iterations in the game’s environment. Both Everyday the Same Dream and Playdead’s Inside used this method. The former removed alternatives to labor that the player had already partaken in from future runs. For instance, once the player had travelled to the graveyard with Homeless they were no longer capable of returning there again as Homeless was removed. Inside, on the other hand, focused on its bonus areas. If any of the bonus devices had been unpowered in one run, they would remain unpowered in the next playthrough. This indicated to the player that the prior playthroughs have had an effect on the world that is tangible. By leaving environmental ghosts, the game is showing that prior cycles have occurred not only to the player separate from the game, but also for the game itself.

Relics of the Past

The other method that has been used to indicate prior runs is that the player has items that existed in the prior cycles at the beginning of the next. A game that uses this method is The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask. The cycle is the three day loop that the player plays through. At the end of each loop, the player can choose one of three options: to let the world be destroyed, to fight the final boss, or to reset time. By choosing to reset time, the player restarts the cycle. Instead of having environmental ghosts, the game indicates that prior cycles occurred by not removing items from the player’s inventory. They remain as relics of the events that occurred in the prior cycles.

While I can only recall these two systems being used to indicate a cyclical narrative, that does not mean that this is an exhaustive list. Cyclical games have been few and far between, so there are very few examples that one has to choose from when examining how these systems work. Despite that, the gist of the rule is understood. The game must acknowledge prior cycles in order for said cycles to have any significance.

Multiple Endings

A cyclical narrative must have an ending that leads back to the beginning of the cycle. However, if this is the only ending in the game then the narrative would go on forever. Every cyclical narrative has a true, dead stop, ending, meaning that there must be at least two endings to the game.

In order for a cycle to end there must be a way to break out of the cycle. At some point, the player will do something that moves them from the circular narrative to a linear narrative. In the case of Everyday the Same Dream, this occurs once all five alternatives to labor have been found. For Majora’s Mask it is when the player travels to the moon to fight Majora. Each of these examples leads to an ending that is different from prior cyclical endings in that it fully ends the narrative.

Note that this is also the key reason that cyclical narratives not only do not, but cannot exist in novel and film. There must be some interaction that breaks the narrative out of its loop. As film and novels do not have audience interaction as a core facet of their narratives, any cyclical narrative would be impossible to break, thus never ending. In film, the closest that one can get to a cyclical narrative is a gif. It loops the same narrative over and over, but ends up as one linear narrative played over and over because there is no possibility for ever having a second ending to terminate the cycle.

The Meta Narrative

Now that we have examined what a cyclical narrative is, one might ask “why does this matter at all?” The answer is that, in every instance of a cyclical narrative, the cycle was used as a means to express something that cannot be expressed via a linear narrative. In Everyday the Same Dream the player had the potential to do the boring and soul crushing action of walking from home to work ad-infinitum. By allowing the player to do this, the game was allowing the player to actually partake in the boredom inherent in having to do the same action over and over again. A linear narrative would never be capable of doing so because there would only be a limited and set number of chances to sit at the player’s desk.

In the case of Inside, the avatar is attempting to escape domination. Even if they were to escape as the blob at the end (which they do not) there would never be any liberation from the system of domination because the player always dominates over the avatar. Thereby, the cyclical struggle shows the struggle between the avatar and the elements within its world that want to control it; whereas the secret ending (the breaking of the cycle) is where the avatar challenges the most fundamental mode of its domination: the player. By having the former be a cyclical narrative, Inside expresses the futility of challenging the small elements that dominate a person (those obvious and immediate) when a transcendental power still dominates them.

Neither of these stories could have been told the same way without the use of the cyclical narrative. They could have been told through a linear storyline, but a cyclical narrative allows the themes to be lived. There is no way that a linear arc can have the player live an element that requires routine to be impressed upon the player.

Respawns and Dark Souls

There are two things that may appear to be cyclical that are not, those being when a player respawns and the new game plus systems. For the former, the answer is simple. There is no narratively significant elements in the time between when a player’s respawn and their death, or what we will call the “respawn loop”. No narrative elements would occur within the respawn loop, thereby having no significance to the narrative. In most instances, a respawn is nothing more than backtracking along a linear narrative. The respawn loop usually does not create memories of past iterations and even when is does (as in Dark Souls as the player drops their souls) there are not multiple narrative endings.

Figure 4: Visualization of the respawn loop.

The respawn loop follows a mass quantum suicide machine approach to the world. This machine is one that is based off the theory that every choice creates an individual multiverse where each multiverse is one of the possible choices that could have been made. The mass quantum suicide machine looks for universes where something occurs and destroys every universe wherein it does not, thereby predicting the future by leaving only the universes where the predictions came true. Respawn loops destroy everything that occurred within the loop, reducing the actions therein to having no narrative significance. The only end that can ever occur is what is chosen by the developer, that almost always being player success.

Now, one might argue that a new game plus system is an example of a cyclical narrative in that there are often relics of the past (player levels and equipment) and a possibility to play new game plus over and over again. However, it must be remembered that this is a narrative arc. Does the new game plus have an effect on the narrative of the game? In most instances this is not the case. New game plus has the player playing through the same linear narrative over again with retained power. While it is not impossible for a new game plus systems to have a cyclical narrative, I have not seen one that does so, and games with systems like those in Dark Souls do not present themselves as cyclical experiences.

Here we have examined a completely new story arc. The cyclical narrative is a potentially powerful tool that developers can use to bring new levels of meaning into their experiences. Not every game needs this system as they are hard to build and useful only to more niche stories. Both the linear and cyclical narrative should be fostered as games progress.

Our everyday experience is one of habit. Cycles played over and over throughout the day. Everyday the Same Dream used cycles to challenge a fundamental aspect of modern life: the work day. I can only imagine what else the cyclical narrative will have in store for us in the future.

Works Cited

Molleindustria, Everyday The Same Dream. Molleindustria, 2009.

Playdead, Inside. Playdead, Jun 29, 2016.

FromSoftware, Dark Souls. Namco Bandai Games, Sept 22, 2011.

Nintendo EAD, The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask. Nintendo, Apr 27, 2000.

Comments

Post a Comment